The enlightening HBO

documentary "Fists of Freedom" will be rebroadcast

for the final times Tuesday and Friday. Those who haven't seen

it should. Those who have seen it should see it again.

The enlightening HBO

documentary "Fists of Freedom" will be rebroadcast

for the final times Tuesday and Friday. Those who haven't seen

it should. Those who have seen it should see it again.

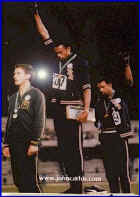

When you understand the

subplots, personal pressures and social climate that led to

the dramatic raised-fist gestures by Tommie Smith and John

Carlos on the victory stand at the '68 Summer Games in Mexico

City, you understand they weren't just gestures by two men,

but an entire track team that cared about more than just

itself.

That's the point Brent

Musburger and many of the journalists who covered the event

couldn't or wouldn't understand. Musburger, then a columnist

for the Chicago American, criticized Smith and Carlos, calling

them, "black-skinned storm troopers." Interviewed

earlier this month by The New York Times about what he had

written 30 years ago, Musburger said his words were, "a

bit harsh," but went on to belittle the act of protest by

saying, "Did it improve anything?"

It's startling that such a

cynical response would come from someone who makes a handsome

living covering black athletes. Perhaps since Musburger is not

"black-skinned" he fails to understand that the

"Fists of Freedom" were, as Smith said, "a plea

for racial justice," not only on the athletic field but

in American society.

For that, Smith, Carlos and the

entire '68 track team should be praised even if it comes 30

years after the fact.

"Did it improve

anything?" Perhaps not to the eye that's unwilling to see

improvement. Certainly, not enough black athletes have become

owners, general managers and coaches of professional sports

teams. But many have. The black athlete of today is not like

the black athlete of the '60s, who was for the most part

forced to do what he or she was told.

To protest meant being banned.

The black athlete of today is more inclined to confront any

hint of racial injustice, though the perpetuated notion is

that they never do enough.

When Tiger Woods and Serena

Williams can win professional golf and tennis tournaments in

the same weekend and prosper in careers established under

their own terms, that's improvement.

When black athletes can command

major dollars in personal contracts and endorsements, that's

improvement.

When an African-American can be

the president of baseball's National League, or become the

president of the NFL Players' Association, or command the kind

of power that Michael Jordan has from basketball, that's

improvement.

All are reaping the fruits in

some fashion from what the black athletes did in the '68

Summer Games, a courageous stand personified by the raised,

gloved fists of Tommie Smith and John Carlos.

The HBO documentary tells us

the gestures came from the black athletes yearning to make a

statement amid the turbulent social and political climate of

that era.

Martin Luther King and Bobby

Kennedy had been assassinated, there were protests over the

war in Vietnam, there were riots in the streets. We learned

that the athletes had discussed boycotting the Olympics before

deciding to make their own individuals protests.

Some wore black socks, some

wore black arm bands, others wore black shoes. But it was the

raised fists of Smith and Carlos that proved most powerful and

provocative. "People thought the victory stand was a hate

message, but it wasn't," Smith said. "It was a cry

for freedom."

To the members of that '68

team, Mexico City remains a endearing period in all of their

lives.

"It was a wake-up call for

me that it was bigger than track and field," said Larry

James, a sprinter and gold medalist on the team. "You

couldn't straddle the fence, either. You had to pick a side.

But all the guys were special in their own right. I wouldn't

trade the experience for anything."

After holding a reunion in

1988, members of the '68 team decided to form an organization

called the International Medalist Association. The

organization consists of black and white Olympians whose

primary objective is to motivate and give wisdom to youth.

"Being Olympians, we talk

to youngsters about life skills," said IMA President Ron

Freeman. The organization is based in Baltimore, but its

influence reaches all the way to Africa, where clinics are

held for young track and field hopefuls.

"We felt there were needs

that haven't been met with respect to utilizing one of the

best resources in the world to fight low self-esteem, drugs

and poverty, which is the Olympic athletes," Freeman

said.

Freeman said the roots of the

organization began in Mexico City, because the idealism is the

same.

"It's about human

rights," he said. "It's about caring about your

fellow man."

Freeman was a member of the

gold medal-winning 4x400 relay team in '68. Carlos is actively

involved in the organization, as is sprinter Lee Evans and

James.

They can be reached through

their website, at www.internationalmedalist.org.

"The '68 team is together,

white and black," Freeman said. "People from that

'68 [team] have had an impact on succeeding teams by giving

them tips and support."

Said James, now the assistant

dean of students and director of athletics at Richard Stockton

College near Atlantic City: "There are 7,000 Olympians in

this country and 2,200 have medals. Each of them have a story

of how they got there. And they've gone on to have other

careers and make contributions to society."

So did the raised fists of John

Carlos and Tommie Smith improve anything? Every single day.

reprinted from the New York

Post

click here for other archive articles

click here for current articles